One of the more fraught decisions virtually every Catholic must face in the modern era is what to do when invited to the invalid wedding of a family member or friend. And while the attendance decision itself can be excruciating, the moral dilemmas pertaining to addressing and accommodating a loved one who entered a make-believe union tend only to multiply in the decades that follow. So a workable policy is a practical necessity. Nevertheless, there is a striking lack of guidance from the Church on these matters, and it’s superlatively frustrating. That said, allow me to provide some resources to guide your decision-making process. By referring to basic principles of moral theology and reflecting on the thoughts of some prominent Catholic voices, a degree of clarity may be achieved.

Language Must Correspond to Truth

Before we tackle the specific question of wedding attendance, let’s look at the bigger picture. If we believe, in accordance with Church teaching, that no marital bond exists in an invalid “marriage” of a loved one, we must never act, in word or deed, as if they’re married. The Eighth Commandment requires us to use language to communicate truth, even when doing so is uncomfortable. This is why Christians can never in good conscience use pronouns reflecting a so-called transgender person’s false identity. Our verbiage must likewise match the truth with regard to a false marriage.

This principle has import for those who wonder how they ought to introduce an invalidly married couple to others. Should our language reflect civil law when it contradicts natural law, such as in “I’d like you to meet my brother and his ‘wife,’ Cindy”? Or are we obliged before God to communicate what we understand to be objectively true, despite what the State and couple aver? For example, “This is Tom and his friend Cindy,” or “Meet my civil sister-in-law, Cindy.” Or, perhaps we could be subtler, with verbiage like, “I’d like you to meet Tom and Cindy.” Let truth be your North Star, not legal fiction.

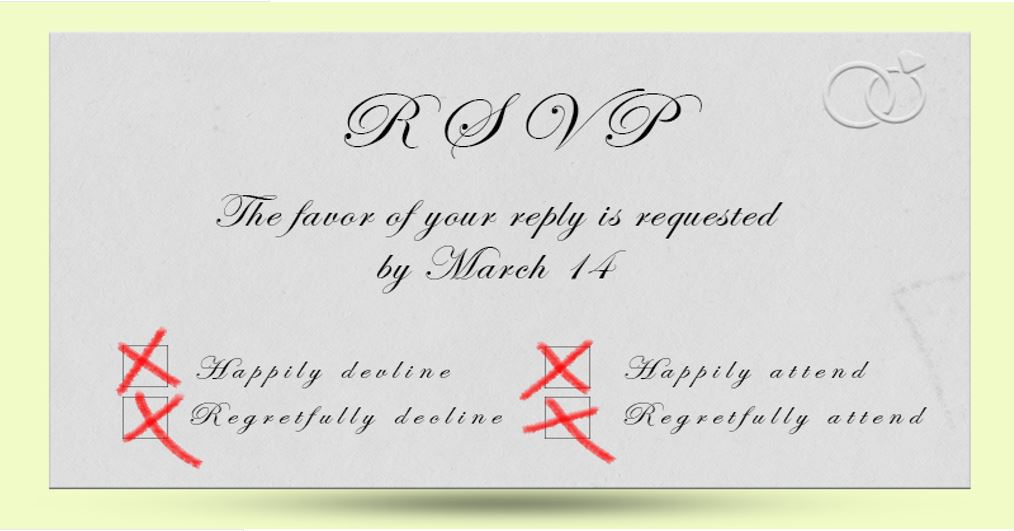

Similar conundrums follow with the written word. For example, addressing the invalidly married loved one and his civilly married partner with invitations for a formal event can be tricky. Should we capitulate and address them as, “Mr. and Mrs. Smith”? Or are we obliged in conscience to address them more accurately, with the acrimonious-sounding “Mr. Tom Smith and guest”? Asked and answered.

And perhaps even more excruciating are decisions that would have to be made if the invalidly married loved one and his civil spouse ask to pay you a long-distance visit. Do you provide them a single room (which, of course, is what they’d expect after years of civil “marriage”)? Or do you risk offending them by insisting they sleep in separate bedrooms? If you suggest a local hotel, your paying for it directly supports their sinful co-sleeping. On the other hand, not paying for it adds an extra expense to their visit, not to mention extra kindling to their ire. How do we best honor God and respect His objective moral order while simultaneously caring for the good of our loved ones? These are difficult questions, but rectitude must not ever be sacrificed.

Obviously, decisions on “wedding” attendance (and the subsequent fallout) could elicit great tension within families, if not outright hostility. Family members formed by the world would ironically see conscientious objection to disordered faux-nuptials as “judgmental” or “anti-Christian.” It goes without saying that none of this matters to the faithful Catholic intent on doing the right thing. But that’s the big question: What is the right thing?

It is truly bewildering that the Church hasn’t given firm guidance on this problem of cosmic proportions. We’ve all been left to our own devices to handle situations that literally wreck families on a regular basis. It’s legitimately hard to balance the obligation to communicate truth with the command to love our neighbor. Do we use the example of John the Baptist challenging King Herod’s living in adultery, which cost John his head (Mark 6:17–18)? Or do we capitulate for the sake of family “harmony,” as most priests today advise?

On the bright side, there’s been at least a little nonmagisterial ink spilled on whether it’s permitted to attend invalid weddings. Even so, as one would suspect, different Catholic thinkers have come to different conclusions. Let’s compare some prominent contemporary opinions on the matter.

The Invalid-Wedding Dilemma

Monsignor Charles Pope, media personality and pastor of Holy Comforter–St. Cyprian Catholic Church in Washington, D.C., argues the general rule is that “Catholics should not attend the weddings of Catholics held outside of the Church, or weddings that are invalid due to other factors.” However, he adds a caveat:

There are, however, some situations where refusing to attend a wedding may so poison family relationships that a prudential judgment can be made to attend. Since the overall goal is to witness to the Catholic faith and to seek conversion and a return to the sacraments for fallen-away Catholics, one may prudently determine that a better course is to attend but resolve to seek to explain, at a later time, the need to validate the marriage to the couple and others.

Father Francis Hoffman, J.C.D., executive editor of Relevant Radio, makes a distinction between couples violating natural law and those “merely” forgoing canon law. Ceremonies celebrating a “union” that contradicts natural law, such as when one party is divorced without an annulment or when both parties are of the same sex, can never be attended by anyone of goodwill. However, he explains, weddings in which baptized Catholics marry without proper form as mandated by the Catholic Church (celebrated in church in the presence of a priest or deacon and two other witnesses), are a little different:

This is the case of two persons who are free to marry, one or both having been baptized as Catholic … but who likely do not practice the Faith for one reason or another. They decide to get married, but not in a Catholic Church, and without the bishop’s dispensation from canonical form. … Such weddings are potentially valid if both parties are free to marry and intend to marry with the properties of unity and indissolubility.

In other words, these weddings are only invalid due to improper canonical form. If the cultural Catholic wills the essentials of marriage but is genuinely ignorant of the objective sin he’s committing by marrying outside the Church without a dispensation, Hoffman says you may be able to attend the illicit union:

If your attendance at this wedding would push the Catholic spouse farther away from the Catholic Church, you may not attend. But if your presence might help bring them closer to the Catholic Church, I think you could attend, so long as you speak up and say something [to them later].

And note that this “speaking up” must have as its end the couple getting right with the Catholic Church. Hoffman adds, “Such a defect of canonical form is easily remedied,” in accord with canon 1160 of the Code of Canon Law.

In another opinion, Dr. Janet Smith, philosopher, author and retired professor of Sacred Heart Catholic Seminary in Detroit, makes the argument that there are rare exceptions in which a Catholic may attend the reception, but not the marriage ceremony, of an invalid wedding:

I don’t believe attendance inherently means approval, even if it will generally be interpreted that way. … Certainly, if you have clearly conveyed to the couple participating in the wedding ceremony that you believe their marriage to be invalid and that that is the reason you will not attend the ceremony, they won’t be able to draw the conclusion that you approve.

Dr. Smith agrees with the sentiment that one shouldn’t attend the celebration of an invalid marriage; but in rare cases, she claims it could be an important opportunity to evangelize family members otherwise rarely seen.

Father Mitch Pacwa, S.J., president of Ignatius Productions, and EWTN teacher and host, notes that while canon law doesn’t expressly prohibit Catholics from attending invalid weddings, those considering attending should not take the discernment process lightly. Pacwa cautions, “Every situation will call upon our reserves of prayer, discernment and evaluation. And a good confession before making any decision is always a good idea.”

These positions contrast with the reigning neo-pagan viewpoint, which misemploys “God’s love” as a cover for licentiousness. One member of this camp, Protestant Amy Grant, a contemporary Christian music artist who gained widespread popularity in the 1980s and 1990s, has been in the news lately for not only her thoughts relating to marriage, but also for her corresponding actions. Indeed, Grant decided to offer her farm for the celebration of the so-called wedding of her lesbian niece and the niece’s partner.

“I love my family; I love those brides [sic],” Grant told The Washington Post in November, adding, “Honestly, from a faith perspective, I do always say, ‘Jesus, you just narrowed it down to two things: Love God and love each other.’ I mean, hey — that’s pretty simple.”

What may not be as simple is admitting to oneself that defining love in a way that supports unnatural behavior and contradicts divine revelation is fatally erroneous. Grant is herself presumed to be in an invalid marriage to fellow musician Vince Gill — both were married to other people (with four children between them) when they met and “fell in love.”

Marriage and the Moral Law

No matter where our sympathies lie in this debate, at a bare minimum, we must give effect to certain universal principles and laws, which will help us avoid cooperating with evil.

Jesus Christ taught in no uncertain terms that marriage is indissoluble. When His disciples asked Him why Moses had allowed divorce, Jesus responded:

Because of your hardness of heart he wrote this commandment for you. But from the beginning of creation, ‘God made them male and female.’ ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.’ So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore, what God has joined together, let no one separate.

He then affirmed the logically necessary truth about divorce: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery against her; and if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery” (Mark 10:5–12).

It is human nature, as designed by God, that once a man and woman become one flesh, they cannot become autonomous individuals again until death. Accordingly, a marriage is ratified by the free consent of the parties to its essential components (in accord with canon 1096) and is consummated (making it unbreakable) with the one-flesh marital embrace.

In addition, as mentioned above, Catholics must marry according to canonical form, meaning in a church with three witnesses, one of whom must be a priest or deacon — unless a special dispensation is granted. Additionally, both marriage partners must be of a certain age (canon 1083), understand the essential components of marriage of unity and indissolubility (canon 1056) and be of sound mind (canon 1095). Each makes sacred promises of lifelong fidelity and openness to children. Marriages of Catholics are presumed valid when these and other essential elements are in place, until or unless a declaration of nullity is granted (canon 1075)

All things considered, marriages of non-Catholics are presumed valid if they’re in accord with natural law and are officiated by a public (civil) authority. If both parties are baptized, they enter a sacramental marriage; if not, the union is held to be a valid natural marriage.

Therefore, a person who validly married but obtained a civil divorce is still married. The marital bond is not dissolved by private or civil renunciation. This means, then, in the objective order, a so-called “remarriage” is actually perpetual adultery. This is because the natural moral law applies to all human beings, not just Christians.

Unity and indissolubility are the essential components of the institution of marriage, natural and sacramental. Christ didn’t abolish natural marriage but raised it to the dignity of a sacrament so that the baptized could become sharers not only of natural life, but also conduits of supernatural life (grace) for each other — and together become a channel of grace for the world.

Cooperation With Evil, and the Law of Love

Since the Church doesn’t have a concrete policy on the perennially sticky question of attendance, Christians are called to use their properly formed consciences. Catholics must take into consideration the meaning of marriage, the disorder of objective adultery, the glory of God and the highest good of all those involved in the invalid event. Every case is generically the same but specifically different.

The law of love, which is based in truth, has as its end the salvation of souls. While Christians must always avoid supporting immorality and injustice even with their bare presence, if the principle of double effect indicates there would be more harm than good caused to souls by not attending, they can consider it. Nonetheless, it may be safe to say those potential situations are rare exceptions to the rule.

Generally speaking, what’s needed most in our time of ambiguity and confusion is for Catholics to stand firm in objective moral truth. We’ve soft-pedaled and watered down the truth for decades, thinking love demands compromise for the ignorant and weak of faith. This has not yielded positive results, leaving in the dark countless souls who want nothing other than to know the truth in order to conform their lives to it.

Prayer and counsel along with prudence and courage are needed in discernment. Then, after a good Confession and Eucharistic Communion, make your move.